Tiberio Grimberg lives on the outskirts of Beka’ot, an Israeli settlement near the Jordan Valley. He works as a gardener, nurturing and watering plants in his moshav. “Around here in the Jordan valley, vineyards dominate the agriculture,” says Tiberio as he wipes his sweat, sitting in the seat of his tractor. The father of six sons has lived in Beka’ot since the seventies. «I found the future in this land. Water wasn’t lacking, and we now have green where there was once the desert,” he explains peacefully. “But the desert is like a jungle; it’s a continuous battle. And the Palestinians are losing it.”

Less than a kilometer away the barren land of the Bedouin breeders stands in stark contrast. The dramatic water shortage is immediately apparent. “To get water we have to go over 25 kilometers every day with the tractor,” explains Abed al Mahdi Salami, the 73 year-old leader of the small Bedouin community of al-Hadidiyah. “We tried to build irrigation for agriculture and livestock with money from the Spanish cooperation. But the Israeli military demolished it for safety reasons,” says Abed gloomily while showing the remains of the pipe. Near his tent, a water pump from the large Israeli utility company, Mekorot, hums away quietly. “The water is there, you see? Why can’t we use it?”

The struggle for water has been at the center of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict for years. The tension erupted into a bona fide crisis in the summer of 2016, when numerous Palestinian villages and refugee camps were without water for days, and had to import water barrels to meet basic needs. They lay awake in the middle of the night, waiting, hoping for the pressure to come back to the pipes. “In the refugee camps, especially in the south towards Hebron – but also in our own – we did not see water for days. No shower for children, useless faucets, not even a drop for sanitary purposes. It was a living hell.” Amjad Rfaie is the director of the New Askar refugee camp, and faces daily the requests and pleas of the inhabitants. “And the Israelis did nothing, in spite of requests to buy water from Mekorot, requests where we were asking to pay. In fact, they even reduced the supplies.”

The Palestinians are heavily dependent on the Israelis for water, in spite of aquifers and rainfall collection basins concentrated in the north-central areas of Palestinian territories. “There is a deep schism in the right to water access between the two populations,” expains Amit Gilutz, spokesperson for B’Tselem, an Israeli organization that works to protect the rights of the Arab population in the occupied territories. “Each new well, even in the territories controlled by the Palestinian Authority, requires a permit from the regional Israeli civil authority (ICA). Water is not equally distributed, and in areas controlled by the Israeli military the Palestinian infrastructure is often damaged or literally destroyed.”

According to the 1995 Oslo Interim Agreement, water distribution between the Israelis and Palestinians should be divided 80 percent to 20 percent, respectively. This was intended as a temporary solution, pending a final treaty that would have created a Palestinian state and defined Israel’s borders. Today the situation has seriously deteriorated, with the Palestinians having access to only 14 percent of the basin’s resources. The shared management between the two political entities is more complicated than ever. “We have all kinds of problems in daily management,” explains Imad Masri, director of The Water Supply and Sanitation Department of Nablus Municipality, the second-largest city in the West Bank. “From the inability to drill new wells because of a six-year freeze on the Israeli-Palestinian Joint Water Committee (JWC), to bureaucracy surrounding infrastructure projects, to the Israeli Customs Department blocking components for water plants. A water pump ordered from Italy has taken over a year and a half to arrive, leaving the reservoirs dry.” (Editor’s note: the JWC was created through the Oslo Accords to coordinate water management.)

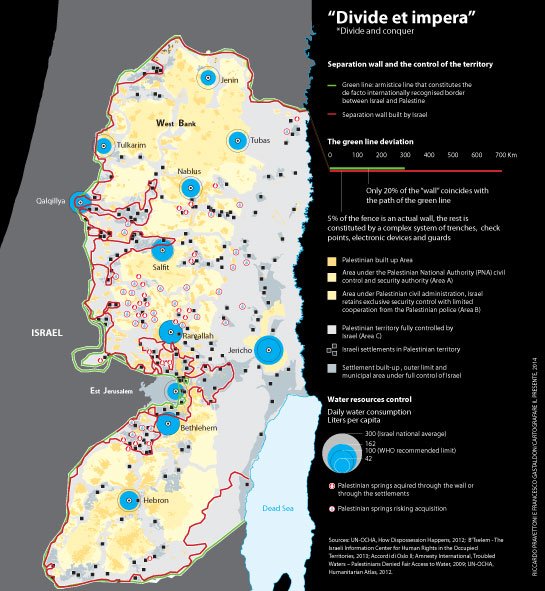

The Palestinian territories are a complex patchwork where it is not always clear who governs and which entities are responsible for administration. The refugee camps are administrated by the United Nations Relief Works Agency (UNRWA) and UNRWA, the UN organization created in 1948 for Palestinian refugees. Area A is under Palestinian Authority control (15 percent of the West Bank territories), while Area B is governed by the Palestinian civil administration and guarded by Israeli/Palestinian joint military control. Area C contains the rest of the Palestinian territories, where the Israeli settlements are also located. Area C is controlled civilly and militarily by Israel. The area totals about 63 percent of the territories, and includes more than 150,000 Palestinian residents and 326,000 Israeli settlers. In this geo-political mess, the highly politicized management of water resources and infrastructure is a true Gordian knot. The Palestinians’ poor maintenance, the Israeli military’s interference, the difficulty of coordinating between several administrative levels – all subtle political ploys – keep tensions high. Meanwhile, the lives of tens of thousands are impacted every day.

Most affected by water scarcity “are rural areas and refugee camps,” says Meg Audette, vice-director of UNRWA Operations, the UN agency dedicated to refugee camps. “The infrastructure is old in the camps and UNRWA has no mandate to be able to create new infrastructures. We can only monitor water quality and make minimal interventions.”

According to Majida Alawneh, water quality department director of the Palestinian Water Authority (PWA), “there are over one hundred critical projects that either have not been approved or have been slowed down by the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) – often supported by international cooperation. Very few new wells have been approved in the past seven years. Meanwhile, water availability has gone from 118 million cubic meters in 1995 to 87 cubic meters in 2014. All this while the population in the West Bank has increased from 1.25 million to 2.7 million inhabitants.

For non-governmental organizations like B’Tselem – and many other Israeli and international NGOs active in the West Bank, like Italy’s COSPE, Oxfam and GVC, “the root of the problem and injustice is in Area C.” So explains Gianni Toma from COSPE, an Italian NGO that has several projects in the West Bank territories. “These areas are harassed by the Israeli army, and forgotten by the Palestinian Authority, which is more interested in developing urban centers like Nablus, Ramallah and Jenin.

In area C, only 16 villages out of 180 are connected to a water supply. “But even then they are not connected to water sources,” continues Amit from B’Tselem, “but only to the Israeli settlements’ water networks. In effect, they become dependent de facto on the Mekorot network, which assigns fixed quotas to the Palestinians, while the Israeli settlements receive water based on demand. The result? During water shortages in the hottest months, the water pressure drops by 40 percent because the settlements have priority. The Palestinians have to wait weeks for water, often receiving it only in the middle of the night.”

In the Bedouin camp near Ein al-Hilweh, in the Jordan Valley’s Area C, Mahmoud has about five hundred sheep. His flock and shepherds need 10 cubic meters of water per day. But his wells are exhausted, and he cannot move because of security reasons imposed by the military, he says, despite the fact that he is a nomadic shepherd.

“We have asked several times to be able to access the water supply, but it is not possible. We own a well but we cannot use it. We cannot leave. And so we are forced to bring in water barrels with tractors. This is destroying us. Over 50 percent of our earnings go into costs for water,” explains Mahmoud. “We also fear that our means will be confiscated by the Israeli army, as has already happened.”

More than 30,000 in Area C live in similar conditions. Many have a water consumption of less than 20 liters per day, shown by UN-OCHA data. The price they pay is steep, too: 400 percent of a normal water bill. More than enough money for additional pumps, given that the water pressure is often insufficient, even at ground level. Often, water supply is cut off because of military exercises, which are announced abruptly.

“The comparison of Ein al-Hilweh with the Israeli Ro’i settlement is merciless,” explains Amit. “Here, Mahmoud’s family consumes less than 20 liters per day. In the settlement, one person consumes over 460 liters.”

Several respondents, both Israeli and Palestinian, who prefer not to reveal their name because of their position and the political sensitivity of the issue, have shared that in reality it’s not only the Israelis who limit the water supply (although 97 projects in the West Bank supported by donor states in the last six years are waiting for approval from Israel). The Palestinian Authority has not taken action to improve the situation. They instead have used the water situation as a political lever against the growth of the settlements, which is constantly increasing, and as a tool to maintain the approval of the population. According to Uri Schor, spokesman for Israel’s Water Authority, it was the Palestinian Authority that did not participate in the Joint Water Committee, the elective venue for negotiating joint strategies between the two peoples. The Palestinian Authority’s absence blocked important projects.

The water issue is addressed in Article 40 of the Oslo Accords, which was a transitional test that was supposed to last a few years at the latest. “Today, this is the only framework that we have available,” says Natasha Carmi, from the Palestine Liberation Organization’s Negotiation Support Unit. “Water is one of the five key points in the accords. The goal is fair use for both peoples, with a balanced per-capita consumption. However, today each Palestinian has on average 70 liters per day, in contrast to 280 liters on average for an Israeli, and 350 liters on average for an inhabitant of an Israeli settlement. 100 liters are the World Health Organization’s threshold for a healthy life. Without access to water, there cannot be an agreement.”

“We are tired of having water used as a political pawn,” explains Mohammad, a student at the University of Bir Zeit. “The Israelis use water as a lever for the occupation, and Abbas’ Palestinian Authority uses it as one of his few levers to preserve the status quo, while remaining incapable of negotiating peace.” Discontent is growing, and the possibility a new water crisis during the summer of 2017 cannot be excluded. Even if Israeli political pressure loosens up, the infrastructure remains decidedly lacking: the wells are on average more than 300 meters deep, difficult to reach, and reserves are increasingly scarce. Water pipes often date back to the Transjordan era, and the treatment plants are insufficient and poorly managed. “The quality of Palestinian infrastructure is worrisome,” says Majida Alawneh of PWA. “We do our best to meet demand.” But hundreds and hundreds of repairs must be made.

According to Uri Schor, the Palestinian stalemate on the Joint Water Committee has delayed development of new infrastructures for years. A fact that underlies the impossibility of satisfying the region’s water demands. Although the Palestinians, judging from local and Palestinian Water Authority administrators, reiterate that the only reason for the water shortage is Israeli military occupation, data from the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics shows that 26 million cubic meters of water are lost in Palestinian water pipes each year. That’s more than 40 percent of all water consumed. The figure represents more than half of Gaza’s water consumption, where the situation has reached the level of a true crisis, particularly as related to hygiene.

The head of Israel’s Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT), Yoav Mordechai, explains in an interview with Haaretz that, “according to Palestinian estimates, 96 percent of the water taken from the aquifer (underground layers of rock containing fresh water) is not really potable. This is why the Palestinians are so dependent on water supplied by Israel. The Palestinian Authority’s wastewater treatment is severely lacking and, according to official estimates, over the next few years there will be a huge shortage of tens of millions of cubic liters of water.” Numerous respondents who prefer anonymity suggest that the economic elites of Ramallah are reaping abundant profits from the water crisis. They are selling purified water at a high price, often from an Israeli utility provider.

Some positive signs must be emphasized. In Nablus, the first large-scale purification plant has been inaugurated thanks to German cooperation. “I think the Israelis understand that this kind of project is beneficial for both of us,” Imad Masri says with a smile. Even dialogue between the two enemies seems to be restarted. After a six-year freeze, the coordinator of government activities in the territories (COGAT), Maj. Gen. Yoav Mordechai, and the Palestinian minister of affairs, Hussein al-Sheikh, signed an agreement on January 15 to renew the Joint Water Committee’s activities to discuss new infrastructure and new plants for drinking water and sewage management. “An agreement that we hope will be the example in many other areas,” says Seth Siegel, author of Let There be Water and a scholar of Israeli water policies. “Israel is a leader in water technology and can do a lot for the Palestinians. The Palestinian Authority’s error has been to not coordinate with the Israelis, making the Palestinians a guilty party. Now, what’s needed is pragmatism.”

For the moment, the lives of Abed al Mahdi and many Bedouins, farmers and Palestinian families remain attached to a non-existent water supply. “This is occupation and political violence,” Mahdi says, while his nephew starts up the tractor. “Nothing has happened since 1948 – what could ever happen today?”

TEXT & VIDEO: Emanuele Bompan

PHOTOGRAPHY: Gianluca Cecere

MAPS: Riccardo Pravettoni

…..

THANKS FOR THE SUPPORT

![]() European Journalism Center

European Journalism Center ![]() IDR Grant

IDR Grant

![]() CapHolding

CapHolding ![]() Fondazione LIDA

Fondazione LIDA

…..

THANKS FOR THE CONTRIBUTIONS

Maririosa Iannelli, University of Genoa